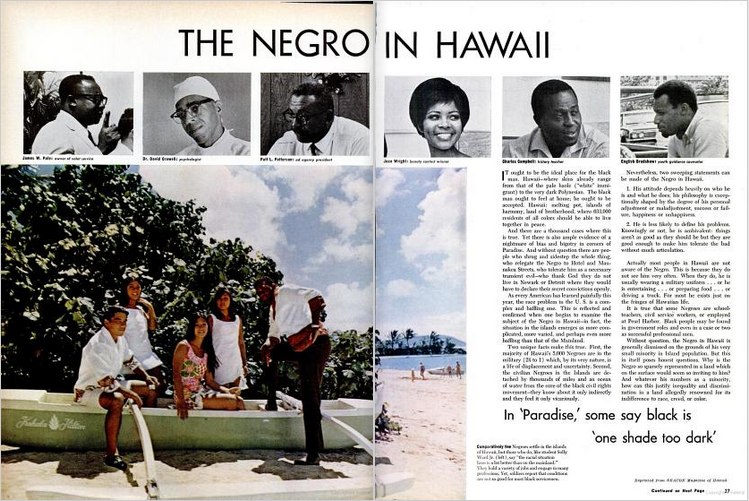

The Negro in Hawai‘i

In 1968 the United States was embroiled in the Vietnam War and domestically cities across the US seethed with violence and repression of anti-war and civil rights actions and organizing. In April of that year King was assassinated and the Civil Rights Act was signed by President Johnson. After a summer of unrest, Ebony magazine published a feature on “The Negro in Hawaii” in its September issue, amid other cover stories like “How the Ghetto Gets Gypped[sic],” “Black Revolt in White Churches,” and “Coretta King: In Her Husband’s Footsteps.” Ebony magazine was first published in 1945 as a monthly periodical with a general interest outlook like Life magazine, but tailored to the Black market. As the lead feature in the magazine’s “Occupations” section, the “Negro in Hawaii” feature focused on Black people who had moved to Hawai‘i and began with acknowledgment of the ambivalence of Blackness in the multicultural landscape of the islands:

"It ought to be the ideal place for the black man. Hawaii—where skins range from that of the pale haole (“white” immigrant) to the very dark Polynesian. The black man ought to feel at home. He ought to feel accepted. Hawaii: melting pot, islands of harmony, land of harmony where 633,000 residents of all colors should be able to live together in peace.

And there are a thousand cases where this is true. Yet there is also ample evidence of a nightmare of bias and bigotry in corners of Paradise. And without question there are people who shrug and sidestep the whole thing, who relegate the Negro to Hotel and Maunakea Streets, who tolerate him as a necessary transient evil—who thank God they do not live in Newark or Detroit where they would have to declare their secret convictions openly. "

Newark and Detroit were sites of major upheaval in July of 1967, both sparked by incidents of police brutality against Black people. For several weeks that summer these major industrial cities burned, many people were killed and injured in the mêlées, and the US was plunged deeper into a national panic about the consequences of Black suppression. The contrast of racially idyllic Honolulu to urban sites of Black unrest was a frequent rhetorical move at the time. It did two things: having been inducted into the Union in 1959, Hawai‘i was a brand-new state and throughout the 1960s there was a major public relations campaign to link Hawai‘i to American identities and consciousness as an accessible paradise where post-WWII Americans could recuperate from mainland life through tourism, by viewing Elvis movies, or by consuming commercial versions of Native Hawaiian culture like hula or by wearing attire like aloha shirts. At the same time, unruly Blacks who demanded human rights and access to civil society in North America were a foil to lei draped, smiling, objectified young women marketed as the emblem of the Islands. In September of 1967, a couple of months after the rebellions in the northern cities, white columnist Drew Peterson reported for his Toledo, Ohio The Blade readership that

What’s happened in Hawaii is a healthy reversal of what’s happening on the mainland. In Detroit, Newark, and other big cities, it’s the young Negro who is the disillusioned troublemaker. In Hawaii, it’s the young generation which is building up a loyal citizenry, setting an example of racial understanding.

Hawai‘i was presented not only as a place devoid of the “young Negro who is the disillusioned troublemaker” but also as a place that was the standard for Asian assimilation into American culture. In White media of the time, young Hawai‘i was the healthy antidote to the intractable conflict between Black and White, but against this rhetorical backdrop, the Ebony article contrasted what Hawai‘i “ought” to be for Black folks with what it was in 1968.

The article frames two major facts about Black people in Hawai‘i as the source of this contrast. In 1968, as now in 2016, the majority of Black people living in Hawai‘i were affiliated with the military and in many ways detached from the Local community. Civilian Black people in Hawaii were, the article says, "detached by thousands of miles and an ocean of water from the core of the black civil rights movement," yielding individuals whose political identities were determined by "his degree of personal adjustment or maladjustment" to life in Hawai‘i, leading to an ambivalence about whether the challenges of being Black in Hawai‘i could actually be articulated. Throughout the article, the Black Hawai‘i residents quoted repeat the experience that while Hawai‘i is not perfect, at least it is not as bad, with regard to how racial violence and discrimination impact daily life, as the mainland: "the balance of good in Hawai‘i over the bad keeps the average Negro from complaining."

The 1968 article both takes and presents "the Negro" in Hawai‘i" as a collection of singular individuals and all male. A common theme is the ease or difficulty Black men in Hawai‘i have in interracial dating and marriage:

How would they [Locals] feel if a Negro bought a house next door? A few had doubts, but again the majority fully accepted the possibility. But then came the question: how would they feel if their daughter dated a Negro... or if she married a Negro. Suddenly the picture changed: the great majority drew the line here. They said, in effect, no dice.

Black women are shown in a photo captioned "Contestants in the University of Hawai‘i's 'Negro Category' beauty contest—the first since 1962." The women are listed by name but none of their stories make it into the feature. The feature also tacitly highlights the disincentive for individual Blacks to imagine themselves as part of a Black community in Hawai‘i where the 'achievement' of finding a non-Black wife is the evidence of acceptance in the larger society.

Strikingly, these echoes from nearly 50 years ago reverberate in Hawai‘i of today. Last year when Hawai‘i was in the running to be the site of Obama's presidential library, an NPR article by Ellen Wu dug into the rhetoric of the Islands as a 'racial paradise,' highlighting that that rhetoric only works if we ignore the racial and imperial motivations in the history of the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, the subsequent and continuing occupation by the US military, and how American interests have treated indigenous Kanaka Māoli, Native Hawaiians. In 1968 as now, being Black in Hawai‘i is something missing from Local conversations about race and ethnicity in this place. When we do talk about Blackness in Hawai‘i, the focus on experiences on the continent that further entrench the idea that anti-Blackness is a a haole, mainland problem, reinforcing the notion that since the pattern of oppression doesn't play out in the same way in Hawai‘i, the Islands are a paradise.

It is interesting to imagine what impact the 1968 Ebony article might have had on the magazine's readership in a time of racial violence and unrest on the mainland. It's unlikely that it spurred a sudden influx of Black Hawai‘i residents with its lukewarm endorsement of the Islands' "don't hate you, but don't want you in my family" orientation to Black people, but in many ways the article erects a different version of Hawai‘i as the racial promised land, albeit with the polish considerably diminished in comparison with that of White writers of the time. Instead of hailing Hawai‘i as the melting pot in which Asian identities are dissolved into American ones (and Polynesians are no consequence), the Ebony article's version of racial paradise is one in which Black people can expect some minimal discrimination, some social alienation, and some of the shadows of American anti-Blackness to follow them across the ocean.

The reality is that contemporary Black identities are complex in ways that are informed by Black identities in the Americas, anti-Blackness in the Pacific, and in ways that are distinctly rooted in the social life of Hawai‘i. There are consequences to people who do not live in Hawai‘i celebrating the forces that make Hawai‘i one of the five best places for Black people to live. The 'best' places are those where there are few Black people and very few opportunities for Black cultural visibility and community. Then as now, the question remains: is the only way for Black people to escape racist violence and approach economic parity with White Americans to be a tiny part of a larger population (2% of Hawai‘i in 1968, ~2% in 2016), to be structurally invisible except for when participating in the military occupation of the Islands?

Full text here.