Pōpolo: a taxonomy

In a first semester Hawaiian language class at the University of Hawai‘i the kumu began a lesson on colors and stative verbs by asking students to name the colors they had learned in grade school Hawaiiana classes. The class pieced together the rhyme ‘ula‘ula, melemele, poni, polu, ‘ele‘ele. Red and yellow were identified with some deliberation by the class. Polu, they guessed, was a borrowing of 'blue' from English. "Pololei. Now what's the word for black?" the kumu asked. Class consensus settled on pōpolo.

Blushing, the kumu apologized to me and the other Black person in the class, a football player from Kona, for our being subjected to our classmates' mistake. He explained that ‘ele‘ele was the word for the black color and pōpolo was the term for the Black person. Then he advised the rest of the class to never say it to a Black person's face.

Years later, volunteering to pull weeds in the nature preserve in the forest of Kalihi Valley, the staff person leading our small group in identifying plants called us to gather around a small shrub with tiny white flowers. Its few green fruits were making the transition to a darker purple and the shape of its leaves marked it as a nightshade, like an eggplant or a pepper. "This is pōpolo," he said, cradling the leaves to pull off some black berries to offer to the girl next to him. He explained that the berries were medicinal, helping respiratory issues. "Sometimes," he said holding the plant, "just touching it can make you breathe easier."

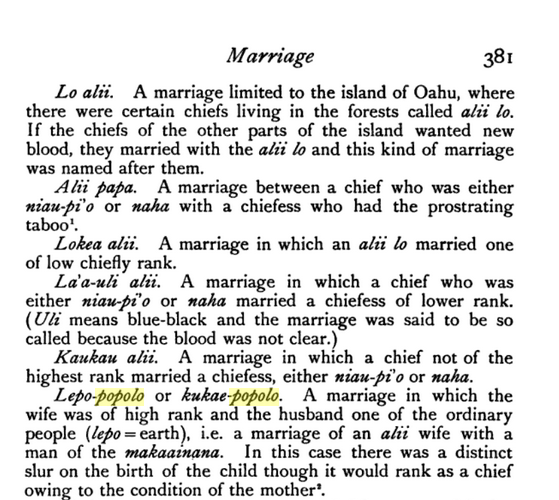

The explanation in Pukui and Elbert's dictionary for the term pōpolo is linked to the often-repeated notion that the color of the pōpolo berries—deep purple—is analogous to the color of the skin of Black people:

pō.polo n. 1. The black nightshade (Solanum nigrum, often incorrectly called S. nodiflorum) a smooth cosmopolitan herb, .3 to .9 m high. It is with ovate leaves, small white flowers, and small black edible berries. In Hawaiʻi, young shoots and leaves are eaten as greens, and the plant is valued for medicine, formerly for ceremonies. (Neal 744). Also polopolo. The fruit is hua pōpolo. ʻolohua, polohua, pūʻili. Because of its color, pōpolo has long been an uncomplimentary term: see lepo pōpolo. In modern slang, Blacks are sometimes referred to as pōpolo. See pōpolohua. (PPN polo, PEP poopolo). 2. An endemic lobelia (Cyanea solanacea), a shrub to 2.5 m high; in young plants the leaves are large, sinuate, thorny on both sides; in mature plants the leaves are unarmed; flowers 5 cm long light-colored; fruit a large orange berry. 3. The native pokeberry. See pōpolo kū mai. 4. Same as maiko, a fish. Niʻihau.

The relationship between pōpolo the plant and pōpolo the ethnonym seems tenable at first, a bit of folklore, like the various explanations of the term haole for White foreigners in Hawai‘i. It seems that pōpolo, as applied to Black people, flourished in the years around WWII when some 30,000 Black service members were stationed in the islands, living in segregated barracks and navigating the racial complexities of this place, as they headed into the Pacific theater of the war.

The dictionary entry notes, "Because of its color, pōpolo has long been an uncomplimentary term," but is there something about the color of a pōpolo's berries that makes it intrinsically off-putting? And how "long" has this been the case since other 'dark' words, like the color term ‘ele‘ele, don't seem to evoke the same negative valences in Hawaiian cosmology?

Joy Enomoto reminds us

The origin of the Kanaka Maoli universe begins with Pō, the deep rich Blackness found at the bottom of the sea and from which all life begins. Pō is the night and the realm of the gods. Mai ka pō mai–of divine origin. One of Maui’s fiercest chiefs, Kahekili, tattooed half of his body black just like his namesake the god of Thunder. Pāʻele kūlani– the chiefly blackening. Pele is the chiefess of both sacred darkness and sacred light–ʻO Pele ia aliʻi o Hawaiʻi, he aliʻi no laʻa uli, no laʻa kea. We did not begin by fearing Blackness, but by revering its power, its sacredness, and its importance to our origins and our strength.

Is the Pō that is the night, the deep Blackness, embedded in the name of the dark berry? Pōpolo is a reflex, or a linguistic descendant, of *Proto-Polynesian polo or poro which linguists and anthropologists hypothesize referred generically to plants of the Solanum genus that bore berries. Languages all around Polynesia have versions of pōpolo:

Proto Nuclear Polynesian: *Poro

REFLEXES IN SOME POLYNESIAN LANGUAGES:

Tongan: Polo (Solanum nigrum [Solanaceae])

Niuean: Polo (Solanum sp.)

Samoan: Polo (S. nigrum, s. ornans; Capsicum frutescens & C. annuum [Solanaceae])

Rapanui: Poporo ("An umbelliferous plant")

Tahitian: Porohiti (Solanim viride cv. anthropopophagorum) & 'oporo ("Pimento" [Capsicum sp.])

Hawaiian: Pōpolo (Solanum nigrum & others [Solanaceae]; Phytolacca sandwicensis [Phytolaccaceae]),

Tuamotuan: Poroporo (Solanum sp. )

Rarotongan: Poro (Solanum americanum, S. capsicoides, S. viride cv. anthropopophagorum)

Maori: Poro, Poroporo, Pōporo (Solanum aviculare; S. laciniatum; S. nodiflorum, S. nigrum) Source

Pōpolo is reflected everywhere in the Pacific and yet in Hawai‘i it has taken on an association with Blackness—and Black foreignness—that twines the plant's shallow roots with racial ideas brought by European settlers. Set to flourish in an environment that saw Black communities and identities as temporary in the landscape of Hawai‘i, White supremacist ideas about Black people as unmoored from land and culture, illegitimate, and on the margins of the human play out in the everyday lives of Black folks in Hawai‘i. Another entry in Pukui and Elbert’s dictionary, nika, is an older term for Black people, borrowed from English in the 19th century:

nika 1. nvs. Nigger, black, blackness, blackened; a term of derision for a marble player who misses a shot. Eng. See ex., kūloku. Keaka nika, minstrel show. 2. Same as māikoiko, a variety of sugar cane. 3. n. A variety of sweet potato; sometimes qualified by the terms ʻeleʻele, keʻokeʻo, nui. Also pāʻele.

Like pōpolo, nika was semantically extended to cover both humans–however dehumanized by the term–and plants. In addition to extension of the word to cover varieties of dark colored sweet things, like sugar cane, a variety of sweet potatoes, this word in Hawaiian also signifies the loser at a game, someone who misses. Borrowed from English, keaka nika, literally "nigger theater," is a minstrel show.

In 1981 Peppo's Pidgin to Da Max became a Hawai‘i best seller as it celebrated the vernacular of much of working class Hawai‘i, Hawai‘i Creole, a language that developed as a result of the superdiversity of the plantation era. Pidgin to Da Max is set up as a picture dictionary with cartoons to match the comic entries, constructing inside joke after inside joke about the words that shape Local experiences in all of the ethnically specific ways Hawai‘i is out-of-sync with English rules and mainland mores.

The entry for "Pōpolo" is simple: "A Local boy–from Harlem." When I used this image in my introductory classes on language in Hawai‘i the entry always got big laughs. And when I asked my students what it meant to them for the pōpolo to be both Local and from a far away neighborhood in Manhattan they understood that "Harlem" was code for Blackness and the "Local boy" was never really Local because Blackness negated it.

Pidgin to Da Max came to Hawai‘i televisions in 1984 when a live action version was produced, with an emphasis on illustrative skits and commercial spoofs. The "Pōpolo" offering was in the form of a commercial for "Pōpolo Suntan Lotion" that transformed a "Vance Mishima" into an Afro-wearing jive-talking brother in an aloha shirt. When Vance's friend is startled to see him so transformed he offers that his suntan lotion has worked the magic and extends it to his nerdy friend who, nervous and off-put, replies that he will stick to Coppertone. Groaning, Vance Mishima swaps the boom box on his shoulder for a spinning basketball on his finger and, pausing to hit a high note mid twirl, warns his buddy, "You're gonna be sorry when basketball season comes around!" The closing of the suntan lotion ad announces, "Pōpolo Suntan Lotion: So effective even your parents won't recognize you," as Vance's mother whispers in astonishment, "Honey, get one pōpolo outside says he's Vance!"

In less than a minute, the idea of the pōpolo is reinforced as funny and foreign and the embodiment of a type of masculinity that is at once athletic, scary, and unknowable. Who knows what Vance was like before his skin, hair, personality, and interests were rendered unrecognizable to his best friend, his parents?

Chronicling her travel from the US to Ghana, Saidiya Hartman’s book Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, reminds us that alienation from kinship, being socially unrecognizable, was a precursor and condition for slavery, which in turn generated and maintained the social category of Blackness in the Atlantic world. Vance being unrecognizable to his mother echoes Blackness as a moment of alienation. Even before they left Africa, kidnapped people who would be enslaved in Europe and North America were separated from their families and cultures. The afterlife of that experience amplifies that separation in ways that few other human migrations and diasporas have, which is why, for example, the practice of Black folks calling non-relatives “brother” and “sister” does not translate easily outside of Black communities.

Back in the Pacific in Pidgin to Da Max’s brief joke Vance puts on Blackness, and however convincing, however menacing, just like a suntan, Vance's Blackness can and will fade. Hawai‘i's ethnic humor is one of the things we all agree people from North America just don't get, but conversely this joke highlights what a Hawai‘i audience might not get beyond stereotypes about Blackness.

That was the 80s. What has changed about Blackness in Hawai‘i in the last 35 years? Hawai‘i has given the world a Black US president and, beyond Obama, many famous Hawai‘i talent exports have connections to Blackness: Kanaka Maoli and Black author and trans activist Janet Mock, Puerto Rican and Filipino performer of Black music Bruno Mars, Black and Samoan actor “The Rock” Dwayne Johnson. One thing those celebrities highlight is the centrality of what I call cases of ‘partitive Blackness,’ wherein Blackness is somehow mitigated by other ethnic and racial identities in a social landscape that values admixture and liberal multiculturalism. In Hawai‘i that means that canonical Blackness—that is, “whole” Blackness—is represented as foreign while mixed-race Blackness can be homegrown, but in a way that privileges the identification with the non-Black part of a person’s racial or ethnic identity.

Northwestern University professor Nitasha Sharma’s current research on Black people in Hawai‘i focuses on “hidden hapas”–Local mixed-race Black people whose existence in Hawai‘i is often obscured by phenotype or by their identification with another part of their multifaceted ethnic identities. There is likely an aspect of this identification with the not-Black part of hidden hapas’ identities that comes from the anti-Blackness that roils just under the surface of Hawai‘i’s multiculturalism in a place where people are not sure, like my Hawaiian language kumu, that the homegrown word for Black is not an epithet.

In a lot of conversations I have had around the Pōpolo Project, I hear both an excitement and a hesitation to be recognized as part of a Black community in Hawai‘i. Though many Black people are visible thanks to phenotype, many feel obscured by the same physical phenomena that would mark them as Black elsewhere. Black folks know that a certain texture of hair, a specific shade of brown on the skin, is not what makes someone socially Black, but in the larger Local community perception of Blackness primarily comes from specific representations of Black people in media that reductively represent Black bodies and cultures in very narrow ways. When given the social leeway to be something else, insisting on representing themselves as Black is risky for many Black folks in Hawai‘i because visibility also brings the possibility of being misapprehended and misunderstood. For many Local people, Blackness is expected to be an urban phenomenon and urban characteristics are attributed to Black bodies in Hawai’i in ways that put them at odds with what we collectively think about and value in our lives here. Emphases on family, devotion to traditional cultural practices, experiences in nature, whether the ocean or the forest, —all are concepts highly valued in Local culture that are usually not packaged as part of the Black experience in the media that represents us.

When we address others with the phrase aloha kākou, we are invoking a relationship, an understanding between us. Language is a place where we struggle, where our values and worldviews come together in our everyday lives. Living in Polynesia has taught me that there is a power in naming “we”—that inclusion and exclusion, whether “we” is “a kākou thing” or mākou, an “us guys, not you thing”—this is fundamental in how humans organize community and how we make sense of the relationships between us and the entities that surround us. I wonder if there is a possibility for Blackness to be recognized as at home in Hawai‘i, as Joy writes, to be recognized as the beginning of all life and the seat of so much fertile possibility. I wonder sometimes what my kumu was thinking when he apologized to me and the football player from Kona. Was he worried that acknowledging that Local folks called us out of our names also acknowledged a category that othered us and exposed a part of Hawai‘i–that thread that gave us keaka nika–that not only made the islands out of sync with the continent but belied the myths of ethnic harmony and perpetual respect that Hawai‘i people tell ourselves and others?

Sometimes, I have heard from Black people of Hawai‘i that pōpolo is just an innocuous Hawai‘i version of “Black,” but I haven’t met one person yet who prefers it as the primary way to describe their own ethnic or racial identity here. I wonder if pōpolo is always for talking about third parties, the way we talk about plants and animals. In the Hawaiian view of the world there are names like ʻāweoweo, the name of a red fish sometimes called “bigeye” and the name of a type of sugar cane and again the name of a type of seaweed. They share the name because they share traits that distinguish them from other entities around them. Many words for plants and animals come in pairs and these doublets help us to see what is true of them both. Pōpolo, whose leaves were famine food and whose black berries stained kapa, the medicine that grows wild in the underbrush and restores the breath on contact. This pōpolo reverberates with its human counterparts, whose Black cultures invigorate politics of sovereignty, shape Local art and culture, and continue to be linkages between Hawai‘i and the rest of the world. Blackness is not always salient in Hawai‘i but it is always there, growing, flowering, ripening, and healing.